Down the Rabbit Hole

Pivotal Arc (Whirlwind Recordings), coming out in a few days, features my evolving language composing for string instruments. It explores the connection between classical and jazz idioms with a Violin Concerto, written for soloist Nathalie Bonin, and a String Quartet written for the Molinari String Quartet. The Concerto was developed over a decade, working closely with the soloist, whereas the Quartet was composed right before the recording session, meeting the performers for the first time at rehearsal. A common thread between them is a focus on imaginative musical risks and finding connections between genres.

Early Inspirations

Near where I grew up in Toronto, Canada, there was a great reference library that had a large vinyl collection of music covering a diverse range of genres and styles. In high school I was getting turned on to so much music by taking out twenty records (the library checkout limit) every few weeks and listening to something new nearly every night. As a budding saxophonist, I was getting clued in to John Coltrane’s music, the 60’s quartet and beyond, thanks to my private teacher, Alex Dean. I had picked up the complete Bartok String Quartets by the Emerson Quartet at the library around the same time. Even though the instrumentation and approach was very different, in many ways I heard a deep connection between them: the intensity, vibrancy, immediacy, melodic elements, rhythmic development and some of the harmonic approaches. Even though Bartok’s music was fully notated, it still has a feeling of improvisation and spontaneity. And even though Trane’s music was highly improvised, it has a deliberate sense of development and form. They both have a vibrant blend of intellect and emotion.

This inspiration from these two sources grew into two of my first albums. Magic Numbers (Songlines), recorded in 2004, incorporates a String Quartet led by Nathalie Bonin with saxophone trio of bassist Mark Helias, drummer Jim Black and myself on tenor and soprano sax. Horizons Ensemble (Musictronic), recorded in 2005, was with pianist John Taylor, improvising cellist Ernst Reijseger and violinists Nathalie Bonin and Parmela Attariwala. For both of these albums, I wanted the strings to be another voice within the ensemble, interjecting and steering the conversation, not always, or even often, in a background role.

In preparation for composing, I dove into the Bartok scores, and also found the Debussy and Ravel String Quartets really helpful. I highly recommend them, in particular for composers coming from a jazz background, as the harmonic language is familiar and the writing and development is quite clear. You get a good sense of the ranges of the instruments and combinations of the four voices. From there I found it easier to then go back to Beethoven Quartets and move ahead to Shostakovich Quartets and beyond.

By digging into the literature, doing the homework, listening and checking out scores I learned a lot, but this is only one key element. As Jim McNeely (via Bob Brookmeyer) mentions in his recent blog post, doing it is also critical. By writing the music and then having the opportunity to hear how the players responded to it, how the registers sounded in real life and how the overtones interacted and resonated, helped immensely to focus and clarify my imagination: so what I was hearing in my mind would better match reality. (I had the good fortune to study with Jim on and off for several years: a great learning experience from one of the best.) This crucial element comes into play later in the story. From these experiences, I was able to take what was effective and discard what was not.

To the Present

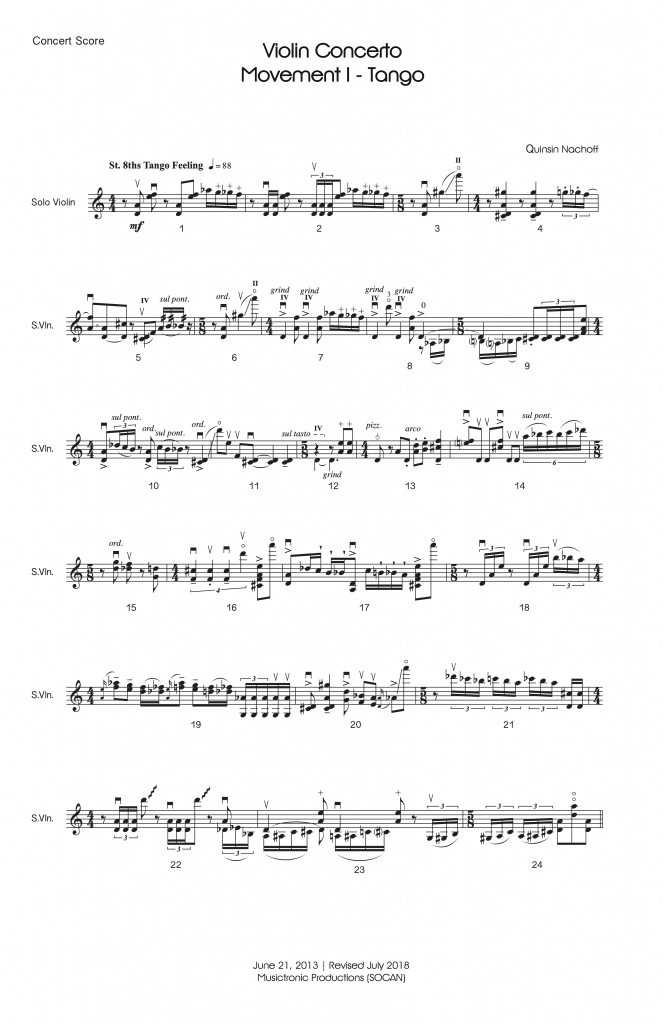

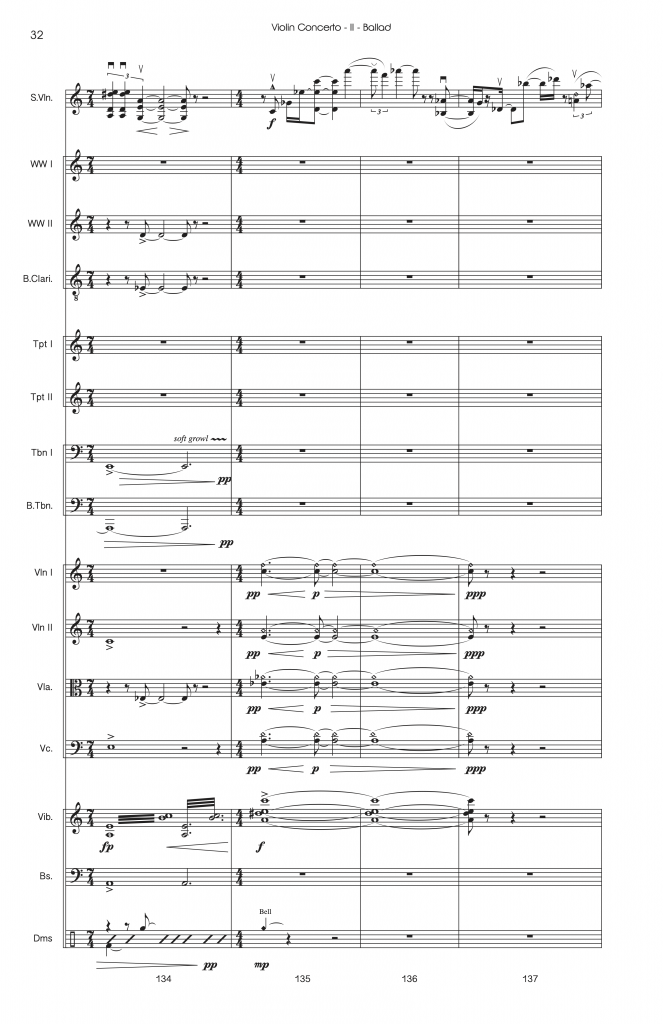

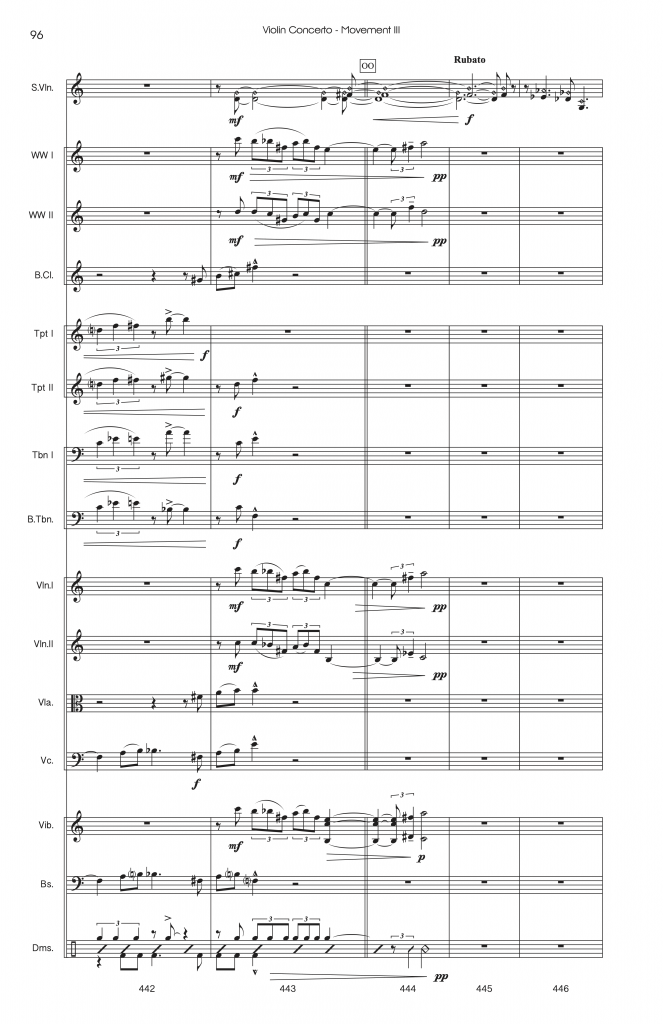

Nathalie had been integral to both of those early albums. She had a strong classical background, but was also interested in improvising and worked in a wide cross-section of styles and ensembles. After a performance, we started tossing the idea around of writing her a concerto that would showcase some of her diverse interests. The commission came about in 2008, thanks to the Canada Council for the Arts. Writing for a specific person and working with her to develop the language was a growing experience. I knew some musical settings she was really good at that I wanted to showcase, such as the abstracted Tango of the first Movement, the moody ballad of the second, with room for her to improvise a cadenza into the third movement. But I also wanted to push her and challenge her with some new directions (it is a Concerto after all!) For example, by incorporating some of my own improvised language coming from the perspective of a jazz saxophonist, or some of my own interests at the time, including exploring Balkan music which manifested in the beginning of the third movement. The Concerto was completed in 2013, demoed in NYC in 2014 and recorded in 2018 in Montreal. (Raising funds to record large ensemble works is no small feat as I am sure many readers here can understand.)

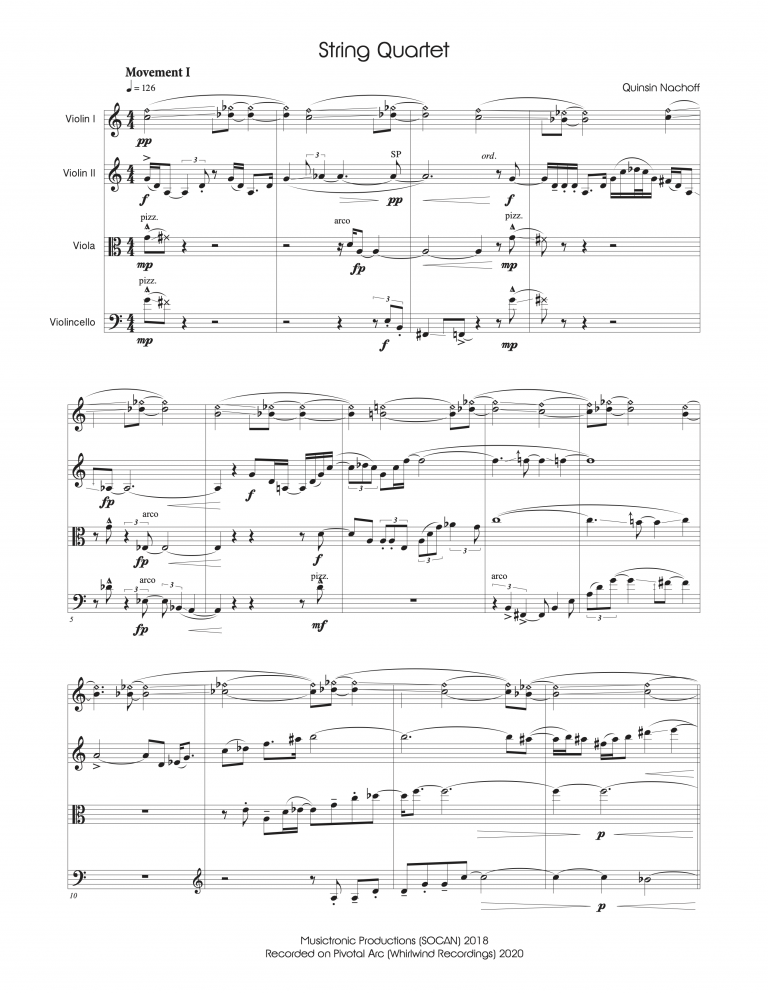

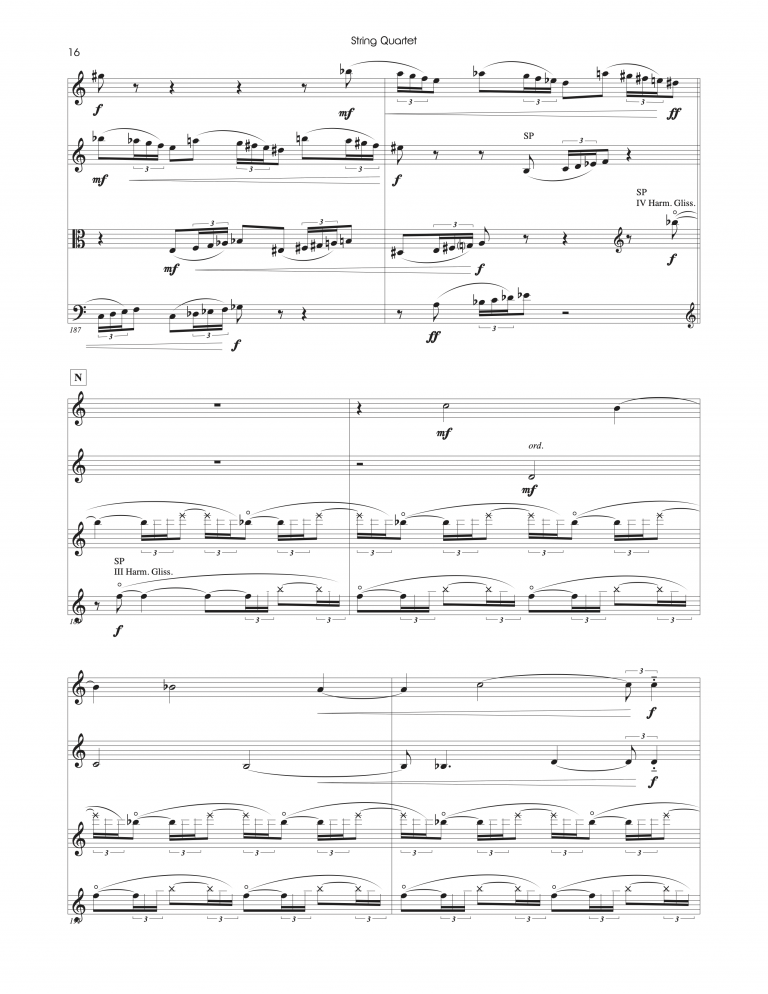

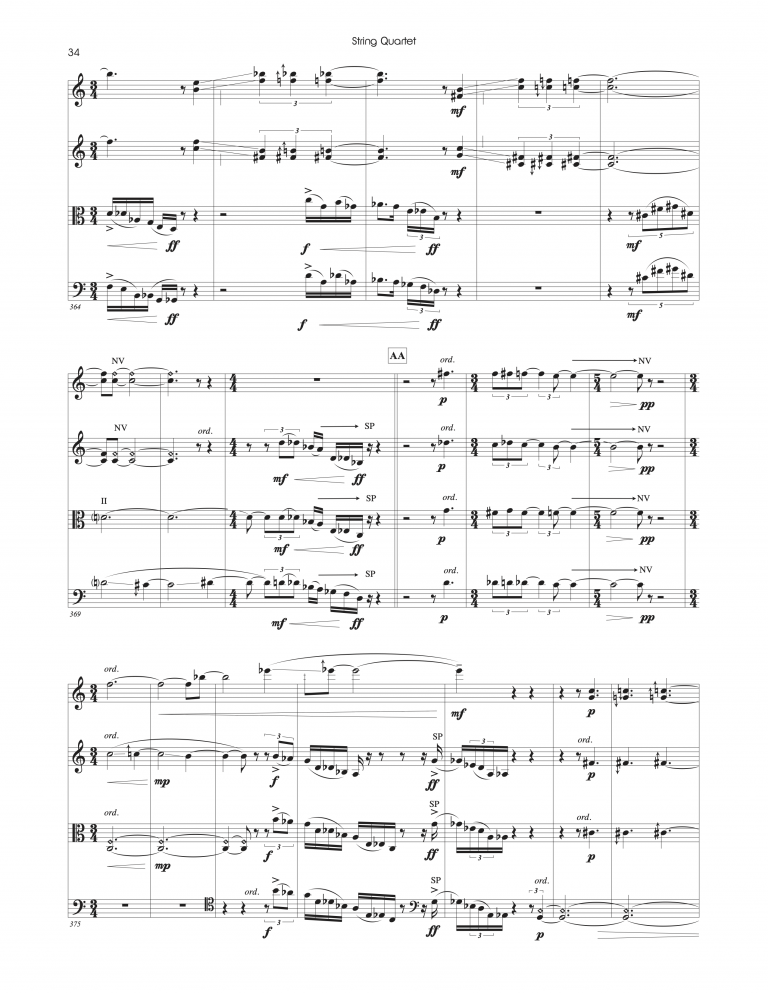

In contrast to the Violin Concerto, which was developed in collaboration with the soloist over several years in addition to a long working relationship, the String Quartet was composed over a short period of time. I had not worked with the Molinari String Quartet before and did not know any of them personally. We were supposed to workshop some of the material together, but because of unexpected delays, the final score was delivered four weeks before the downbeat and I did not have the opportunity to hear any of it before our first rehearsal. Everything needed to work, as there would not be time to revise parts or rewrite sections. I had checked out the Quartet’s previous recordings that included works by Kurtág, Schnittke, R. Murray Schafer, Gubaidulina and knew they were working on an upcoming album of John Zorn’s music. I was confident that they were comfortable dealing with a complex notated language. They are not improvisers, so this would be a fully notated work. This would be a companion piece to the Violin Concerto, so to maintain some unity, I decided each movement would be a mini-concerto for one of the four players, in this order: Violin II for Movement I, Viola for Movement II, Cello for Movement III and Violin I to close out the work.

In writing the piece I still wanted to push myself and take musical risks, but calculated ones. At the first rehearsal, after only hearing the first few measures, I was very happy, and extremely relieved (!), to discover that all of the effects/extended techniques I imagined worked! Theoretically I knew these all should work and imagined what they would sound like, but sometimes in practice the dynamic balance does not quite work or executing a concept can be technically problematic. Thanks to earlier experiences of writing and working with strings my internal imagination was now much more matched with reality. While listening to the quartet play, I became fascinated with how much liberty each player would take in their featured movement. Each time we ran through it in rehearsal or did a take in the studio, they would subtly change the emphasis or push and pull the time in a different way – keeping it really fresh and with a sense of improvisation.

Translating the Thought Process

Rather than settling on a single element, I will discuss one short section from each movement of the Concerto and String Quartet, drawing some parallels to my background as a jazz saxophonist or revealing some of my thought processes.

Violin Concerto – Movement I – Opening Violin Cadenza